Ecology

One of the many great things about camping is the chance to spend time in different ecosystems and explore landscapes with interesting flora and fauna.

A local guidebook can be invaluable for learning more about the ecology of the area you’re visiting. Below are some of the plants we encounter frequently in our travels.

Sagebrush

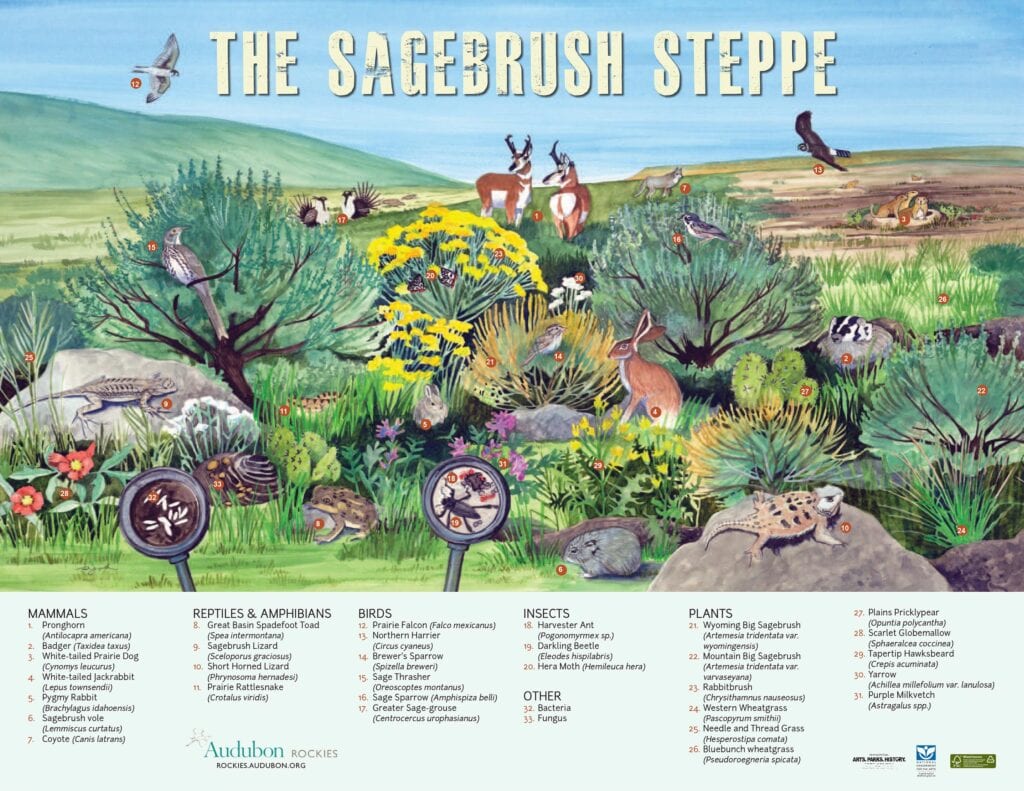

Sagebrush is an emblematic plant of the West, covering 165 million acres across 14 states ranging from Washington to New Mexico. Its leaves are a source of food for deer, pronghorn antelope, elk, jackrabbit, bighorn sheep, and birds—in fact, hundreds of species depend on sagebrush.

Multiple species and subspecies of sagebrush grow in the West. The plants can reach 100 years old. Their longevity is somewhat surprising given their diminutive height (the plants usually stand less than 2 feet high). Sagebrush tap roots extend 1 to 4 meters into the ground. Ingeniously, these roots lift deep soil moisture to near the surface during the day and at nighttime release the moisture, which is then available for the plant’s own diffuse root system as well as roots of nearby plants.

People have made extensive use of sagebrush. The Navajo have used it to treat headaches, indigestion, and fever, among many other ailments. Settlers in the West found sagebrush useful for treating bullet wounds, while cowboys used it for cologne. Some people have sought relief from the flu by steeping the leaves in tequila and sipping frequently!

Sagebrush is so iconic to the American West that the plant appears on the state flag of Nevada. Yet sagebrush landscapes are changing as homes are built, oil and gas drilling expands, and wildfires burn with increasing frequency. After wildfires, invasive species that are less favorable for native wildlife, like cheatgrass, often replace sagebrush.

Aspen are found throughout the American West, in the northern reaches of the Midwest and Eastern U.S., as well as in much of Canada. In fact, the quaking aspen is more widely distributed than any other native tree species on the continent. According to Audrey DeLella Benedict, “Aspen is one of the few plant species that can grow in every ecological zone except alpine tundra.” Oddly, the tree is rather fragile, being susceptible to snow damage and windthrow.

Aspen typically grow by means of root sprouting, which produces clones. Clone groups are distinguishable based on leaf shape, fall color, and other characteristics. An aspen clone called “Pando” in southern Utah is a single organism covering 100 acres, weighing more than 14 million pounds, and clocking in at 80,000 years old.

Many plants and animals depend on aspen forests. An individual beaver may consume about 1,500 pounds of aspen bark each year. Fungal diseases are common in aspen, causing the development of cavities that serve as homes for a wide variety of birds like owls, wrens, swallows, bluebirds, nuthatches, and chickadees. In the winter, small rodents like mice and voles may munch on aspen bark located under the snowpack, where they forage for food while awaiting spring. Elk are also prolific eaters of aspen bark, causing extensive scarring on trunks. Bears sometimes climb aspen trees to dine on bird eggs and nestlings, leaving distinctive claw marks.

Aspen forests are in jeopardy, with many stands in Colorado and Arizona seeing massive diebacks. The decline is thought to be related to droughts.

Sources

- Audrey DeLella Benedict. The Naturalist’s Guide to the Southern Rockies. Fulcrum Publishing: 2008.

- U.S. Forest Service page on Aspen Decline.

- Data Basin. Map of Aspen Range.